If you have never recorded your own ECG, here I'm going to give a photo tour of how I do it. I happen to be using the OpenBCI system, but you can do the same thing with nearly any EEG system. For example, when I first got my OpenEEG board from Olimex, I tested with ECG. It worked just fine.

|

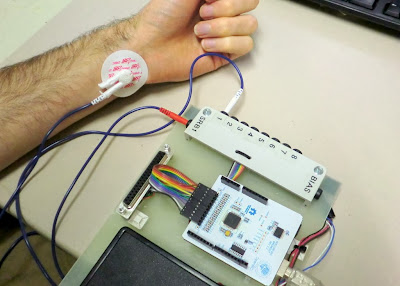

| Using OpenBCI to Record my Heart Signals (ECG) from my Left Wrist and Right Wrist (my right wrist not shown because it is holding the camera!) |

ECG Overview

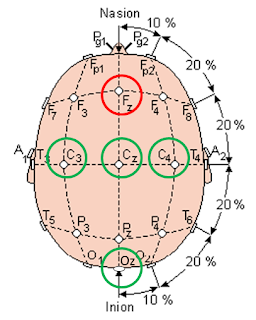

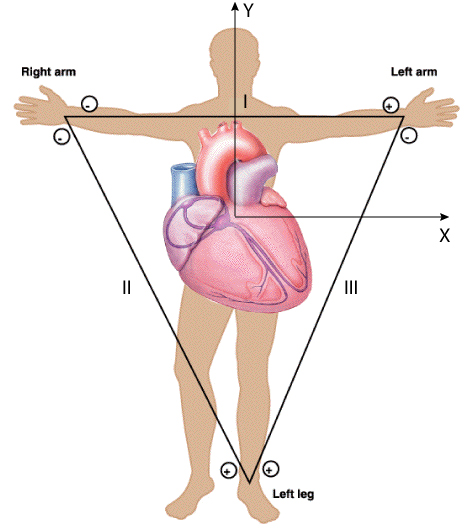

EEG is the measurement of the electrical signals generated by your brain. By contrast, ECG is the measurement of the electrical signals generated by your heart. When the heart contracts, it generates a relatively strong electrical gradient in your body. With electrodes on your skin, you can measure the difference in potential (ie, voltage) across your body caused by your heart. That's what the ECG records.

|

| ECG Can Be Measured Across Many Locations. I'm going to use my two wrists. |

Hardware Needed

To measure one's ECG, you need electrodes to attach to your skin, you need wires to connect the electrodes to your electronics, you need some signal acquisition electronics that are appropriate for biosignals, and you need a computer and some software to record and visualize the ECG signals. I'm going to talk about each of these elements in the sections that follow.

Electrodes: Electrodes are simply pieces of metal that are electrically connected to your skin. As long as you make good contact, nearly anything can be used as an electrode...they do not have to be specific to ECG. If you don't want to get ECG electrodes, you could use EEG electrodes, you could use a piece of copper tape, or you can even use a piece of bare wire (if you can keep it attached to your skin). But, I want to make this easy for myself, so I'm going to use cheap, disposable ECG electrodes.

I like the disposable ECG electrodes because they are self-adhesive, they come with conductive gel already attached, and they have a nice little button snap for attaching lead wires. They can be purchased from many, many places on-line. One source is BioPac, where they are $0.38 each. You can find them even cheaper, if you search around.

|

|

| Self-Adhesive Disposable ECG Electrodes Stuck to my Wrists. |

Since my EEG electrodes have the same 1.5 mm touchproof plugs as my ECG lead wires, it made sense to me to invest the time and money to buy the mating touchproof jacks. I bought some 1.5 mm touchproof jacks from PlasticsOne. I happened to buy the panel-mount version, but PCB mount would also be a good choice. At over $3 each, these are not cheap. They are convenient, though. I mounted the jacks to a scrap piece of plastic and soldered on some wires to go to my electronics. Easy.

Electronics: The whole point of this exercise is to use my heart signals as a way of testing my EEG electronics. So, for me, I'll be using EEG electronics (OpenBCI, OpenEEG, whatever). But, if you were just doing ECG, ECG signals are generally stronger, which means that the electronics do not need to have such low self-noise. As a result, ECG electronics tend to be cheaper than EEG electronics. Regardless, I'm using EEG electronics. In this case, I'm using OpenBCI.

For my setup, I connect one lead wire to "Input 1" (the "+" input) and one lead wire to the common reference input, "SRB" (the "-" input). See the picture below.

Computer and Software: Obviously, any computer will work...you just need one that will connect to your ECG/EEG electronics. OpenBCI interfaces to the computer via an Arduino Uno. That part is easy. The harder part is what software to use on the PC. You could use the custom displays that we have made for OpenBCI. Or, following up from my last post, you could use BrainBay, which is an open source biosignal analysis program for Windows. I recently wrote a software interface for OpenBCI to allow its data to be received and processed by BrainBay. That's what I'm going to use here.

ECG Results

With the setup that I described above, I started BrainBay, relaxed my wrists (muscle contractions make electricity, too, which can mask the ECG signal), and watched my ECG data scroll by on the BrainBay display. Some example data is shown below. It should the ECG signal recorded for four heart beats. It's always comforting to scientifically confirm that one's heart is beating.

|

| ECG Signal Recorded using OpenBCI and Visualized using BrainBay. |

Compared to the challenges in measuring EEG signals from the scalp, I find that ECG is way easier to measure reliably. That's why I use it as my first test of an EEG system. If I stick electrodes on my wrists and don't see a signal like that shown above, I know that something is wrong with the electronics and not my body. If you find yourself hacking EEG systems for fun, you might want to consider using this technique as well. Plus, you might learn something about ECG and your heart, which is cool, too!

Follow-Up: In trying my homemade electrodes, I used ECG as my first test.

Follow-Up: I also was able to measure EOG using a similar setup.

Follow-Up: I've now tried to share the data from this post on my github. Try it!