Neurosky Mindwave Electrode Setup: I don't own a Neurosky Mindwave so I can't use that hardware to explore these "concentration" brain waves. But, I do have an OpenBCI system, and it's pretty flexible, so I'll try that instead. The main question is how to setup the electrodes. Looking at the videos for the Mindwave, and looking at the Sparkfun hack pages, the Mindwave appears to use an electrode on the forehead and then another on an ear clip. I'm assuming that the one on the ear clip is the reference electrode. It does not appear to use a bias electrode, probably because they found that it was not needed for this body-mounted, battery-powered system.

OpenBCI Electrode Setup: To mimic the Mindwave setup, I put a gold cup electrode on my forehead and another on my left ear lobe. The one on my forehead was plugged into Channel 1 of my OpenBCI board and the one on my ear lobe was used as the reference. Because my system is not battery powered, I did use a bias electrode, which was an ear clip electrode placed on my right ear lobe (this is the first time I've tried the ear clip electrodes). I also chose to stick another gold cup electrode on the back of my head, just to see what happened back there during this experiment. Oh, and to attach my electrodes, I used standard Ten20 conductive paste. My impedance check showed about 30 kOhm for each electrode, so not too bad.

|

| Using OpenBCI (V2), 3 gold cup electrodes, and one ear clip. Oh, and some guy's brain, too. |

Procedure: Watching Nick's video, he says that he is able to trigger the Mindwave's concentration detector by mentally counting backwards by 3, starting from 100. This sounds pretty straight-forward and he clearly had good success with it. Frankly, I was a little more skeptical about my own ability to make it happen. So, in my data, to make it clear to me where I was trying to concentrate, I closed my eyes for a short period before and after my mental counting. I did this because, by closing my eyes, I would generate strong alpha waves (10 Hz) that would clearly show up in the data. As a result, after the test, I could look for the data between the two alpha wave recordings...this would be the period when I was concentrating. Let's see what I got.

My First Look at the Data: The spectrogram below shows how I typically look at an EEG recording for the first time. Note that frequency is on the vertical axis and time is on the horizontal axis. You can definitely see the signature of the alpha waves (that horizontal stripe around 10 Hz) at the beginning and at the end of my recording. In the middle is the period of time when I was concentrating. In this plot, I don't see anything interesting during the concentration portion of the test. I just see some "noise" that looks little different from everything around it. Bummer.

|

| You can definitely see the alpha waves from my eyes being closed. Good. But, is anything happening during concentration? |

Higher Frequencies? But then I remembered reading somewhere (like in one of my own early posts?) that "concentration" was usually seen as increased activity in the higher EEG frequencies -- the so-called Beta waves (13-30 Hz). So, I replotted the data where, this time, I zoomed way out on the frequency axis. As you can see below, I'm now showing zero to 100 Hz. In this new plot, you can clearly see that there is more EEG activity when I was concentrating compared to when I was not. Now we're getting somewhere!

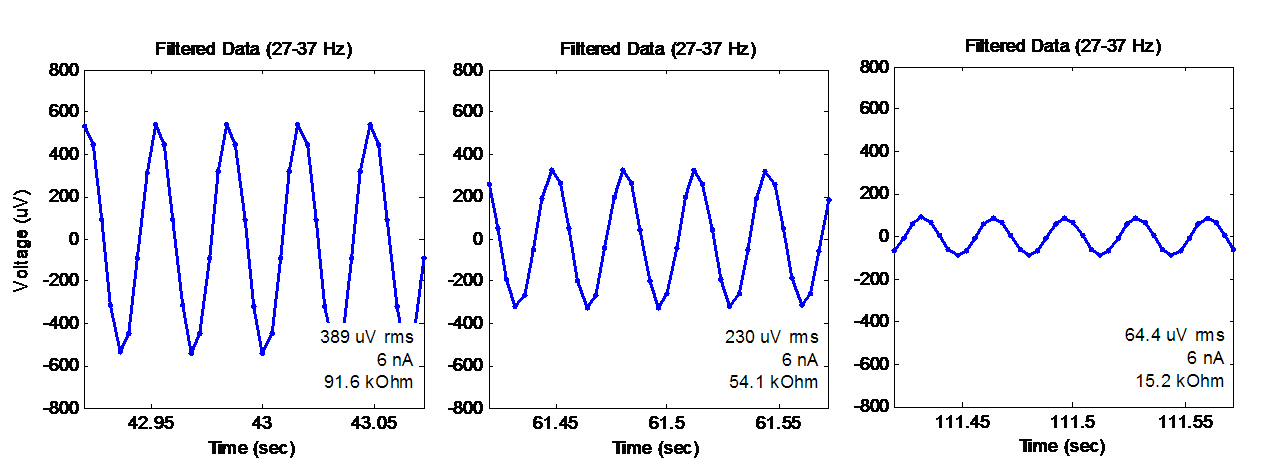

Comparing the Spectra: While spectrograms like the one above are helpful for quick qualitative views of both time and frequency, it is difficult to be quantitative with a spectrogram. So, in the plot below, I show the average spectrum for a period of strong concentration (t = 90-130 sec) and I show the average spectrum for a period where my eyes were closed and my mind was especially quiet (t = 155-178 sec). As can be seen below, the two spectra are definitely different, especially for frequencies above 22 Hz.

Detecting Concentration: With the knowledge that, in my brain, "concentration" starts to show itself as increased EEG energy above 22 Hz, I can now contemplate building a concentration detector. The key is to filter my EEG data so that I can assess the intensity of EEG activity in frequencies above 22 Hz. Then, I'd pick a threshold to which I can compare the EEG intensity level. If my EEG signals are stronger than my threshold, my detector would say that I am concentrating. If I'm weaker than the threshold, my detector would say that I am not concentrating. Sounds pretty easy, right?

Applying to My Recorded Data: In the figure below, I apply this idea to the data that we've been discussing. The top plot is the same spectrogram that I showed below. The bottom plot is what happens when I filter the EEG data to show the intensity just for frequencies between 22 and 100 Hz. You can see, the trace does indeed move up and down to reflect whether I'm concentrating or not. Specifically, for the sustained concentration (t = 90-130 sec), my filtered EEG signal is running about 3.4 uVrms. Then, when I close my eyes and relax (after t = 140 sec), my EEG signals drop down to about 2.0 uVrms. So, if I were to define a threshold for detecting concentration, I might put it somewhere in the middle...say, around 2,7 uVrms.

|

| Measuring the EEG amplitude in the 22-100 Hz frequency band. Note how it is low while my eyes are closed and that it goes higher while concentrating. |

Feeling Some Success: The plot above is making me pretty excited. It suggests that I have conscious control over my EEG signals. To date, I've only had strong success with controlling my Alpha waves (by opening and closing my eyes). I've also had some small success with Mu waves, but they're really hard for me to get. So, seeing this concentration-induced Beta (13-30 Hz) and Gamma (30-100 Hz) is pretty darned exciting.

Criticism: A critic reading this post might argue that I have not proven any link to concentration. A critic might say that the increased high frequency EEG energy could just be a natural result of opening my eyes. Based on the data shown so far, that would be a fair criticism.

Gathering More Eyes-Open Data: To counter this criticism, the data below is from another test that I performed using the same setup. In this test, I performed a similar procedure where I started with my eyes closed, had a period with my eyes open, and then finished with my eyes closed. Unlike the previous test, though, I did not do my concentration exercise during the eyes-open period. As a result, we should be able to see whether the increased high-frequency EEG activity is due to concentration or due to simply having my eyes open.

Not Concentrating: In the plot above, you can see that there is a trend in my EEG signal strength, but that it is not related to the opening of my eyes. At the beginning, when my eyes were closed, my high-frequency EEG signals were pretty low at 1.9 uVrms. Then, when I opened my eyes (t = 210 sec), my EEG intensity increase only slightly to 2.0 uVrms and stayed that way for quite a while. I think that this is strong evidence that simply opening your eyes does not specifically trigger increased Beta and Gamma activity.

Wandering Mind: In the second half of my eyes-open period, we do see that my EEG intensity drifts upward. Eventually, it averages about 2.5 uVrms. Perhaps this increase reflects that I got bored and started thinking about my next EEG test. Regardless of the reason, you'll note that even the increase to 2.5 uVrms still does not exceed the 2.7 uVrms threshold that we set a couple of paragraphs ago. So, this small increase does not meet our criteria for "concentration".

Conclusion: I think that this second data set is good evidence to declare that intense (>2.7 uVrms) Beta and Gamma activity is not due simply to opening my eyes. I am feeling pretty confident that the intense high frequency EEG activity seen in the first data set is due to my concentration. This means that Beta and Gamma activity is under my conscious control, which is the most exciting EEG result that I've had in a long time.

Next Steps: Being under conscious control means that I could potentially use "concentration" as part of a brain-computer interface for future hacks. I'm always looking for ways that I can try to control things in the physical world using just my brain waves. Perhaps with some practice, I could use this technique to compete with Nick Poole in a spoon-bending competition!

Follow-Up: I recorded my concentration level while eating breakfast, and found some really cool changes!

Follow-Up: Interested in getting the data from this post? Try downloading it from my github!